by cr_threeillusions | Feb 27, 2013 | Blog

If you’ve ever spent five minutes around Advaita (translation ‘non-duality’, from Advaita Vedanta, a school of Hindu philosophy dating from the 5th century http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nondualism), you’ll have heard people say that your true nature is awareness or consciousness.

What do Advaitans really mean when they talk about “awareness” and “consciousness”? Those words typically refer to something that happens inside the brain but that obviously isn’t what Advaitans mean. So what do they mean?

I remember that when I first started attending Bob’s meetings 25 years ago (sailorbobadamson.com), I struggled to make sense of the terminology. All these years later, I sit in rooms and still see new people still trying to work out what the hell the old timers mean when they say “awareness”, “consciousness” or ” intelligence energy”.

I don’t blame them – it all sounds quite mystical and reminds me of Catholics talking about ‘the holy spirit’.

As mentioned earlier, when most regular people talk about intelligence, awareness and consciousness, they are referring to something that happens in their brains. And yet Advaita tells us that we aren’t the body – so if I’m not the body, and therefore not the brain, how can I be something that happens in the brain? Press most Advaitans on this subject and they will struggle, eventually trying to make the case that the awareness or the consciousness exists prior to and in the absence of the brain.

And then we wonder why the new people get confused. How can something that happens in the brain happen without a brain?

When people stick around Advaita long enough and perform some serious self-enquiry, they eventually end up realizing that they aren’t what they once thought they were and , quite naturally, they want to share what they have learned with others. (By the way, I think this is a bad idea and recommend at least ten years of silence after realisation, but that’s another subject.) They haven’t given it time to really sink in, so they don’t really have their own way of explaining it. They borrow the terminology they learned from their teachers.

Those teachers, of course, borrowed their terminology from their teachers, and so on and so forth, back hundreds of years to some old, uneducated guy (by modern standards) sitting in a hut in India. This old guy in India knew nothing about the brain or the mind or neuroscience by modern standards. He (or she) tried to explain what he perceived directly about the nature of Self in the best ways and with the best language he had available.

This language has come down to us, hundreds of years later, translated as “awareness” and “consciousness” and “intelligence energy”. However, in Western countries in the 21st century, these words have definitions with which most people are familiar and they are closely associated with the functioning of the brain.

Hundreds of years ago, people didn’t really understand the role of the brain in consciousness. As everyone is aware, for much of human history, people thought that the heart was the centre of emotions and, often, intelligence. We still tell people to “think with the heart” when we want them to get in tune with their emotions.

Neuroscience, however, has made great strides in the last 50 years and we can be pretty confident that it is the brain, not the heart, that is the centre of intelligence, awareness and consciousness (even though how consciousness actually works is still a great scientific puzzle).

The old gurus of India probably didn’t know about the connection between consciousness and the brain. Times have changed and Advaita needs to catch up.

When Advaitans say “everything is awareness” or “you are consciousness”, they are trying to explain that everything in the world that you are aware of, including other people, inanimate objects and, most importantly, your ideas about yourself, appears in your awareness. And what do they mean by “your awareness”?

Words like “awareness” and “consciousness”, when used in Advaita, are synonyms for what cognitive science would call “the subconscious mind” or, even better, to avoid Freudian associations of repressed memories, “the unconscious mind”.

The unconscious mind is the part of our brain that absorbs all of the raw data inputs from the senses. It is noticing everything that is happening in your immediate environment, even if you aren’t consciously aware of it. It is dealing with things that you don’t need to think about consciously.

From Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unconscious_cognition):

It has been well established that the unconscious plays a vital role in perception and data analysis. The numerous examples of optical illusions, hallucinations and other tricks that the unconscious brain plays on the conscious brain provide ample evidence of the active role of the unconscious mind during data gathering and analysis. Several experiments have been performed to show that the unconscious brain is able to gather data at a much faster rate than the conscious brain and also that the unconscious brain filters out a great amount of information and can uses this information to influence cognitive decision making processes.

So the unconscious brain (the operations of the brain that we aren’t conscious of), processes a gazillion data inputs every second. When the brain decides some event is worthy of your attention, it is passed from the unconscious mind through to the conscious mind. That is when it becomes a conscious thought, something of which we are aware.

Here’s an example: when you are driving your car or performing another kind of routine task, you are making tens or hundreds of tiny decisions every moment, most of which you aren’t even consciously aware of – brake, accelerate, indicate, check mirror, look at the speedometer, etc. We can all do these things while having a conversation, listening to an interview on the radio and eating a burger. The unconscious takes over because these functions have been programmed into our brains via repetition over years.

I can have a shower in the morning while thinking about my day’s activities, hardly dwelling at all about what I’m actually doing in the shower. There’s no need to bother my conscious mind with the mundane aspects of washing my body.

When a new human baby is born, its brain has already developed to the stage of performing autonomic functions. Newborns’ brains allow babies to do many things, including breathe, eat, sleep, see, hear, smell, make noise, feel sensations, and recognize the people close to them. But the majority of brain growth and development takes place after birth, especially in the higher brain regions involved in regulating emotions, language, and abstract thought.

When Advaitans use words like “awareness” and “consciousness”, they are referring to the lower functions of the brain. It is the prefrontal cortex, which develops from age 2 – 17, that allows for abstract thought, language and what Advaitans commonly refer to as “the mind”. This is where the ego, a collection of ideas about what and who you are, resides.

What Advaitans refer to as “pure consciousness” is really just sitting in a state where the conscious mind is silent yet the functioning of the unconscious mind remains active. When the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain mostly responsible for planning complex cognitive behaviour, personality expression, decision making and moderating social behaviour) is quiet, we are left with the “awareness” or “consciousness” – i.e. the unconscious mind. I would argue that when Advaitans ask “what comes before thought”, they are referring to the lower brain functions, the older part of the brain. What is aware of the thoughts? It is the brain, the unconscious mind. When Advaitans say “it cannot be understood with the mind”, they are partly correct, because the conscious mind, the part of the brain we use to ‘understand’, cannot understand the unconscious mind because it isn’t aware of it. However, what we can understand with the conscious mind is that the conscious mind isn’t the answer, that it has been living under an illusion all your life, that all of the problems you (as a conceptual individual) have are the result of the conscious mind believing in the illusion and that the only solution is to let go of the illusion.

Of course, we can accept, as most Advaitans are happy to do, that consciousness is the primum movens, the first cause, and that it is all there is. There is no brain in which the consciousness appears – the brain, instead, appears inside the consciousness. The consciousness is all there is.

Some people, however, are going to struggle with that. I confess that I’m one of those. All is not lost for those people however.

Let’s accept for the moment that consciousness and awareness are the functioning of the brain. Learning to live in that place of awareness, aware that the world of solid objects and people is merely an illusion of the senses, a series of mental contracts, will bring anyone who tries it to a place of permanent peace.

However if we are left with consciousness being the functioning of the brain, where does that leave us with respect to the central idea of non-duality, i.e. that we are one with the universe (from the latin uni = one. versus = to turn, “turned into one”)?

There are two simple ways of explaining this.

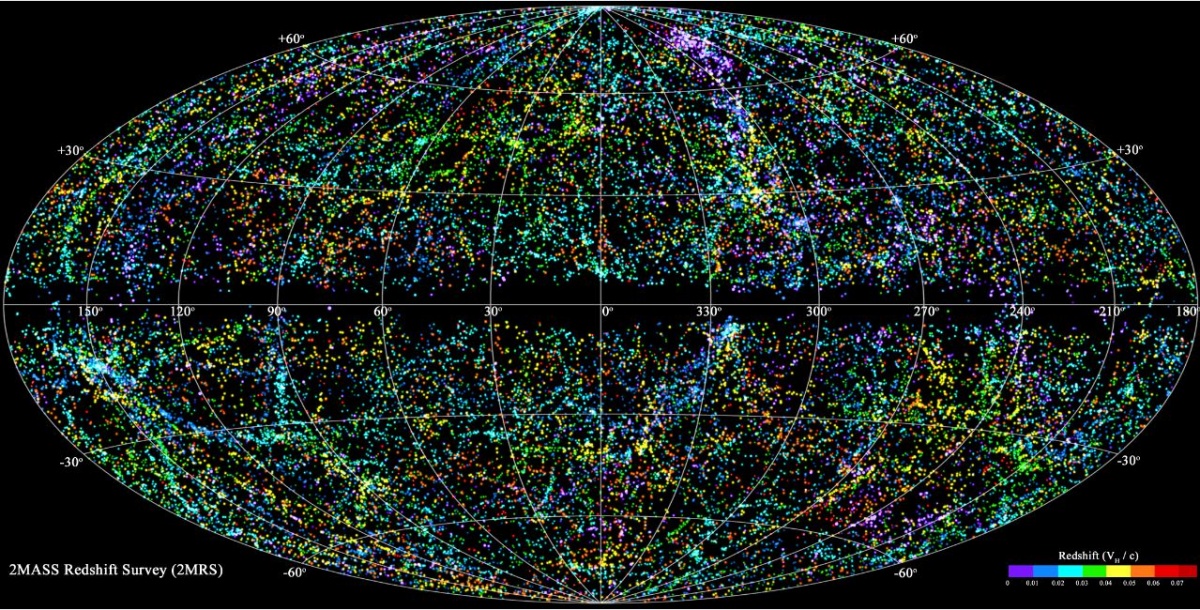

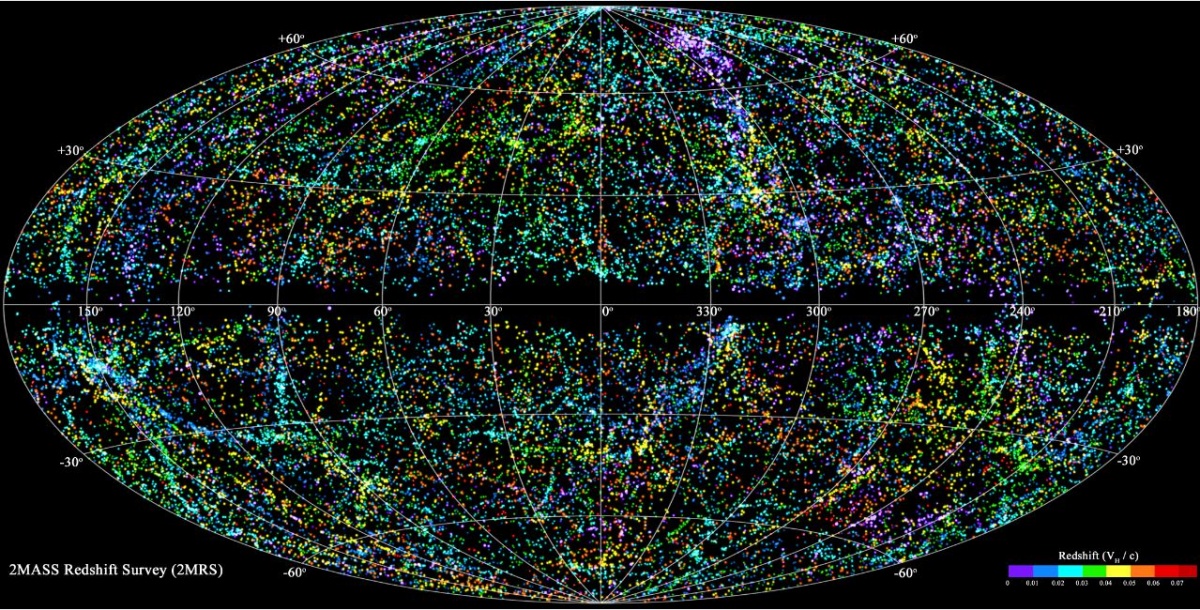

The first is a scientific explanation for what the Advaitans are trying to point towards. When we realise that the entire world that we perceive is being created in our minds – that other people, inanimate objects and, most importantly, our ideas about ourself, are merely mental constructs – then we can say, in a manner, that the entire world appears in our minds (substitute ‘awareness’ or ‘consciousness’ here if you like as they are synonyms). From a scientific perspective, this is totally supportable. Quantum physicists agree that the solid world that are perceived by our senses and then interpreted by our brains is also an illusion. The world we think of as solid is actually made of atoms, which are mostly empty space. They also know that atoms don’t have a hard shell like an egg. Instead, the electrons that orbit the nucleus have a fuzzy perimeter, referred to as a ‘probability wave’. If your eyes were powerful enough to see at a sub-atomic level, and you looked down at your body, you wouldn’t see a separation between you, the air around you, and the floor beneath you. The fuzzy perimeters of the atoms would all blend into one another. In other words, the world of solid matter that we perceive is created in our minds, as they receive a limited amount of data being fed into them by our senses. It is an illusion created by our minds and “we” – the independent entities we think ourselves to be – are also part of that illusion. Ipso facto – everything in the world is the product of your mind. It is all one consciousness, one awareness, manufactured by the one mind – and even the idea of that mind is contained in the consciousness, the ‘you’ that you think you are.

The second way of explaining the oneness is an extension of the first and might be more satisfying to people who cannot accept that the world perceived (albeit incorrectly) by our senses isn’t real at some level and is somehow external to “me”.

Atoms are made of sub-atomic particles, such as protons, neutrons and electrons. Quantum physicists have discovered that all sub-atomic particles spend most of the time existing as probability waves – not actually particles as we usually think of them. A probability wave literally exists everywhere in universe simultaneously until perceived. If the stuff you are made of exists everywhere in the universe simultaneously, doesn’t that mean you are the universe?

The “you” that you think you are, is obviously an illusion. And yet, you are. As Descartes pithily framed it – “I think, therefore I am”. If you didn’t exist, you wouldn’t be able to say “I don’t exist.”

by cr_threeillusions | Feb 4, 2013 | Blog, Enlightenment

Once upon a time, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a long, long way from the shore, on a very still day, while the sun was shining with all its might, there appeared a wave.

Why did the wave appear right then and there? Well I don’t know, to be honest. I’m not an expert on waves. I’m not a waveologist. I’m not even sure waveologist a real word.

All you need to know right now is that a wave did appear, quite suddenly and out of the blue.

What did the wave do? Well from what I heard (I wasn’t there), the first thing the wave did was stick up its head and look around.

“Hmmm, where am I?” it asked to no-one in particular because, well, there was no-one to ask.

Everywhere the wave looked, all it could see was blue. Blue, blue, blue. Blue up above, blue down below, blue as far as it could see.

“I’m must be in the middle of the blue,” the wave decided, quite correctly.

“Now that I’ve decided where I am,” the wave concluded “I guess I should also figure out what I am.”

This turned out to be a much harder problem. When the wave looked down at its body, it realized that it, also, was blue, just like the blue it could see up and down and sideways. After much consideration, the wave decided that even though it was blue, just as everything else was blue, that it must be different somehow from the rest of the blue because it was standing up above the rest of the blue.

“I am a wave!”, the wave decided. This was a pretty impressive leap of logic, I must say. “I am a wave and I’m pretty special,” the wave declared to nobody in particular.

Just at that moment, a great wind started to blow behind the wave, and it gathered a little more energy and grew a little larger. “Wow,” the wave thought to itself. “Did you see what I just did? I made myself larger and faster!” As the wave couldn’t see the wind, it didn’t realise that it had nothing to do with the new burst of energy. Neither did it stop to wonder how it became stronger and faster – this was too complex for a young wave to think about. It just decided that it did these things itself. That was the simplest answer, even though it didn’t stand up to much inquiry. Waves, after all, aren’t known for their big IQ.

“I am a most excellent wave,” said the wave out loud to itself.

After a few minutes of surfing and waving, the wave became a little bored out there in the great blue by itself. Fortunately, at that exact moment, another wave suddenly appeared beside it!

“Well hello, new wave!”, said the wave.

“Ummm hi,” replied the new wave. “Where am I?”

“You’re in the blue,” replied the wave.

“Oh I see,” said the new wave. “And what am I?”

“You are a wave, just like me,” answered the first wave.

“A wave?” asked the new wave. “What does a wave do?”

“Oh well, we can do all sorts of amazing things,” the first wave assured the new wave. Fortunately, at that exact moment, another great wind blew up behind the first wave and made it larger and faster.

“See what I just did?”, the first wave asked the new wave. “I’m sure that’s just a small part of what we can do.”

As the wind was behind both of them, the new wave also grew faster and larger at the same time.

“You do learn quickly!” the first wave congratulated the new wave.

And from that moment on, the two waves became the very best of friends, because what waves like more than anything is to be complimented.

The waves spent the next few minutes rolling and waving and surfing and having a great old time. As a few minutes is actually close to the lifetime of a wave, it seemed to them like they had been together for a very, very long time, out there in the great blue (time, after all, is relative). During this relative very, very long time, they had concluded that waves were, in fact, the most special thing in the entire blue. They decided that the entire blue had been created by the wave god just for them. They also decided that the wave god loved them so much that it gave them the ability to think and act independently of the rest of the blue – the waves called this “free will”.

As they approached the shore, an old, mighty, white albatross soared above them. “Hello white flying thing!” the waves shouted in unison. “What are you?”

“I am an albatross,” replied the albatross, quite appropriately, for it was indeed an albatross.

“Okay then, albatross. We are very pleased to meet you,” responded the waves. “We are waves and we have been out here alone together for many, many years, so you know, it’s good to meet something else.”

“Oh my,” said the albatross. “I have been watching you from the shore and I can assure you that you only appeared in the ocean a few minutes ago.”

“The ocean?” the waves asked, confused by this new information. “What is the ocean?”

“The ocean is what you both are,” replied the albatross. “You are simply bumps on the ocean. Nothing more and nothing less.”

“Nonsense,” scolded the waves. “You obviously don’t know what you are talking about. We are waves. The entire blue was created especially for us by the wave gods. We are the most special thing in the entire blue. We have free will and everything.”

“Oh my,” said the albatross for the second time, trying not to be rude. “I know it must seem that way to you, but I assure you that I have seen thousands of waves come and go during my life and I have sailed across the ocean for many, many years. From up here I see things from a much different perspective. Waves are just blips in the ocean. Without the ocean you wouldn’t exist. You are not separate from the ocean, my dear friends. You are merely the ocean briefly observing itself.”

The waves were quite stunned by this news and, although they didn’t really take the albatross seriously, they were interested in hearing more.

“When you say you have seen waves come and go, what do you mean? What happens to waves?” they asked.

“Do you see that long, white line that you are racing towards?” the albatross asked. “That white line is called the shore. When you reach it, you will vanish.”

“Vanish?” the waves asked in horror. “Will we die?”

“My dear waves,” the albatross purred in his most gentle voice. “You cannot die because you were never alive in the first place. You are the ocean, not the wave.”

The waves thought about that for a minute and were about to reject the entire premise as ridiculous when they crashed into the shoreline and

“Hmmm, where am I?” asked a new wave to no-one in particular.

Photo Credit: Jon Sullivan

by cr_threeillusions | Feb 4, 2013 | Blog

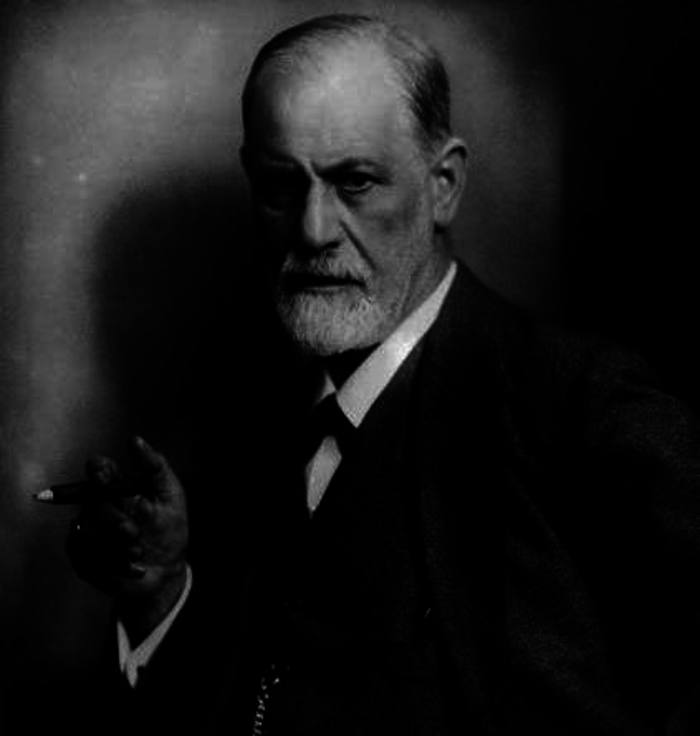

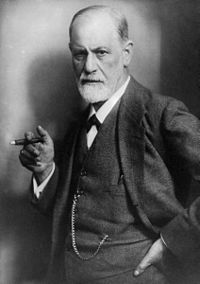

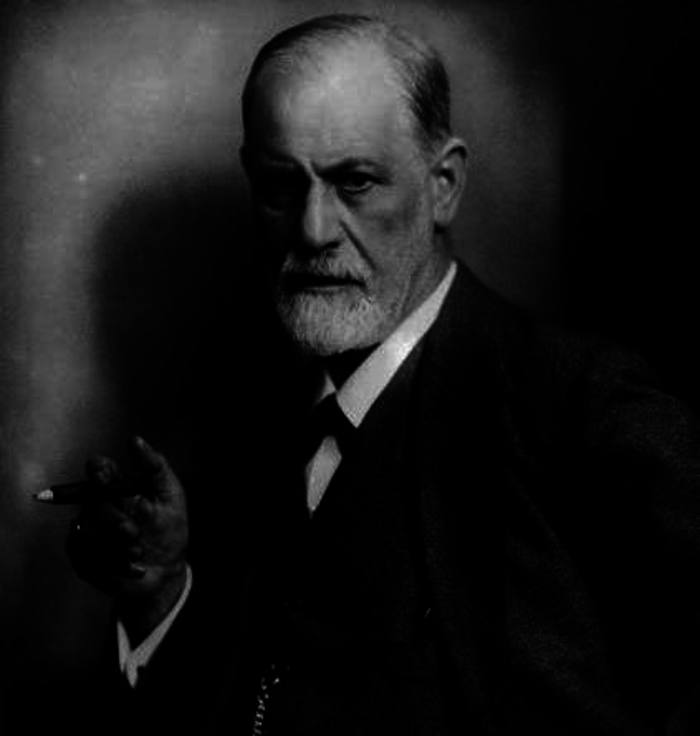

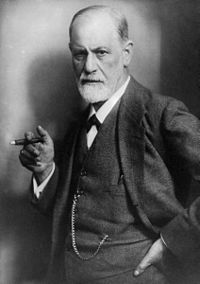

I am grateful to Árni Sigurðsson for introducing me to the conversations between Romain Rolland and Sigmund Freud. Rolland was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist, art historian and mystic who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. He was also strongly influenced by the Vedanta philosophy of India, primarily through the works of Swami Vivekananda, and he shared his experiences in a series of letters to Freud.

Consequently, the first chapter of Freud’s 1929 book “Civilization And Its Discontents” speaks of Rolland’s feeling of oneness with the universe. Freud then goes on to try to explain it in terms of ego.

He starts by talking about Rolland’s sense of oneness with the universe.

This was a particular feeling of which he himself was never free, which he had found confirmed by many others and which he assumed was shared by millions, a feeling that he was inclined to call a sense of ‘eternity’, a feeling of something limitless, unbounded – as it were ‘oceanic’. This feeling was a purely subjective fact, not an article of faith; no assurance of personal immortality attached to it, but it was the source of the religious energy that was seized upon by the various churches and religious systems, directed into particular channels and certainly consumed by them. On the basis of this oceanic feeling alone one was entitled to call oneself religious, even if one rejected every belief and illusion.

The universe is, by definition, eternal (because time started with the creation of the universe) and infinite (because all of space is contained within this universe), and because each of us is this entire universe, we too are eternal and infinite.

It is a feeling, then, of being indissolubly bound up with and belonging to the whole of the world outside oneself.

Normally we are sure of nothing so much as a sense of self, of our own ego. This ego appears to us autonomous, uniform and clearly set off against everything else. It was psychoanalytic research that first taught us that this was a delusion, that in face the ego extends inwards, with no clear boundary, into an unconscious psychical entity that we call the id, and for which it serves, so to speak, as a façade.

I think a whole bunch of gurus and zen masters worked out that the ego was an illusion many centuries before Freud developed psychoanalysis, but hey, let’s not pick his ego apart. 🙂

The new-born child does not at first separate his ego from an outside world that is the source of the feelings flowing towards him. He gradually learns to do this, prompted by various stimuli. It must make the strongest impression on him that some sources of stimulation, which he will later recognise as his own physical organs, can convey sensations to him at any time, while other things – including what he most craves, his mother’s breast – are temporarily removed from him and can be summoned back only be a cry for help. In this way the ego is for the first time confronted with an ‘object’, something that exists ‘out there’ and can be forced to manifest itself only through a particular action.

That seems to me like a pretty clear explanation for how the this of duality develops in a child. When we are born, before the pre-frontal cortex has finished developing, there is no sense of “me” or “not me”. There is only “everything”, being uniformly witnessed in the moment. Hunger comes and goes. Laughter comes and goes. There is no worry, no anger, no anxiety, no stress. Only being in the moment. Once the conscious mind develops, and we learn the concepts of “me” and “not me” (in other words, the ego), these negative emotions develop also.

We learn how to distinguish between the internal, which belongs to the ego, and the external, which comes from the world outside, through deliberate control of our sensory activity and appropriate muscular action.

In this way, then, the ego detaches itself from the external world. Or, to put it more correctly, the ego is originally all-inclusive, but later it separates off an external world from itself. Our present sense of self is thus only a shrunken residue of a far more comprehensive, indeed all-embracing feeling, which corresponded to a more intimate bond between the ego and the world around it. If we may assume that his primary sense of self has survived, to a greater or lesser extent, in the mental life of many people, it would coexist, as a kind of counterpart with the narrower, more sharply defined sense of self belonging to the years of maturity, and the ideational content appropriate to it would be precisely those notions of limitlessness and oneness with the universe – the very notions used by my friend to elucidate the ‘oceanic’ feeling.

For my money, this is a pretty good articulation of non-duality from Freud who also says in this chapter that he, personally, does not have the oceanic experience, although I would argue that we *all* have it as it is our original nature (as Freud himself points out in the book). We all have it – it’s just that for most people, the oceanic experience is drowned out by the chattering of the pre-frontal cortex, the monkey mind, and it’s concepts about “me” and “not me”. The quiet sense of oneness lies underneath the monkey mind, always watching, listening, accepting, staying in the moment.

We have all experienced this now and then – when playing a great game of chess, or doing yoga, or playing violin – and we notice that the chatter has stopped for a while, that we are in “the zone” or “flow”, just being NOW and DOING, without thinking about it or about ourselves.

That is the state that some of us live in permanently. And you can too.